The RBA is one of several central banks meeting this week, and along with Peru's BCRP, is in the minority likely to be sitting tight on its current settings.

European, Swiss and Canadian central banks are all expected to cut.

Brazil is the serious outlier where a 75bp hike is tipped, although the market wouldn't be totally surprised with a jumbo 100bp hike.

So why is the RBA likely to again stay parked with a cash rate of 4.35% given last week's weak Q3 GDP numbers?

Basically, the two key sets of data, inflation and employment, haven't shifted enough to encourage the RBA to shift itself.

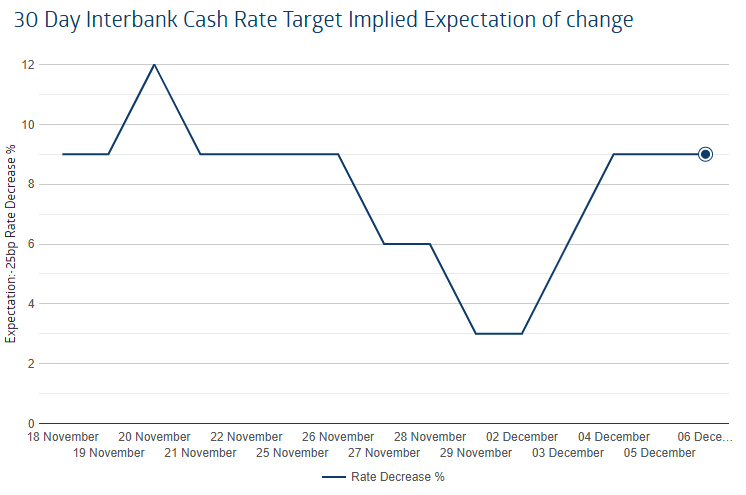

There is a chance of a cut, but it is pretty slim.

Before the GDP figures showing insipid growth of 0.8% year-on-year, it was only a 3% chance. After the national accounts dropped, the likelihood of a cut edged up to 9%.

As HSBC economist and former RBA staffer Paul Bloxham said, it would be typical to think that weaker than expected growth means downward pressure on inflation.

However, digging into the figures, Mr Bloxham points out that while demand is weaker than expected, so is supply, as evidenced by weaker than expected labour productivity.

The RBA had expected productivity growth at 1% YoY. It got 0.8% YoY.

"If demand is weaker, but supply is weaker too, then the inflationary pressures are unlikely to be falling any faster than was previously thought," Mr Bloxham said.

"One way to observe this is that unit labour cost growth is still too strong.

"Although it has slowed to 4.3% YoY in Q3, that rate is still well above the rate needed to be consistent with the RBA's 2-3% inflation target."

The fact that headline inflation is now 2.1% isn't that relevant.

Of greater concern to the RBA is the core inflation measure, or trimmed mean inflation, which pricked up from 3.2% to 3.5% at last count.

Mr Bloxham also says the RBA will have little time for the argument that the economy is only growing at all thanks to public sector spending.

"Although weak private demand is a clear sign that tightened monetary policy is working, if this is being offset by strong public spending, it still leaves demand running too strongly for supply in the economy," he said.

"Whether inflation is being boosted by private or public spending should make little difference to the central bank, unless one is deemed to be more temporary than another.

"With an election looming by May 2025, we see it as hard to argue that public spending will slow anytime soon."

J.P. Morgan's Ben Jarman argues while the RBA board is very likely to keep the cash rate steady this week, prospects for a first cut in early 2025 are firming.

"Governor Bullock will still have to engage with the fact that growth has been subdued for some time and the consumer has showed relative restraint this year, compared to the accruing positives for household disposable income growth," Mr Jarman said.

The J.P. Morgan house view is a lot of noise in the inflation data will be muted in fourth quarter CPI figures and the trimmed mean measure will come at 2.5%, right in the middle of the RBA's comfort zone.

"We expect Governor Bullock to acknowledge that capacity pressure has faded, while retaining some residual uncertainty about inflation," Mr Jaman said.

"Given our inflation forecast for 4Q and evidence of broader normalisation in the basket, we expect January's data will be enough for the board to deliver a first cut in February."

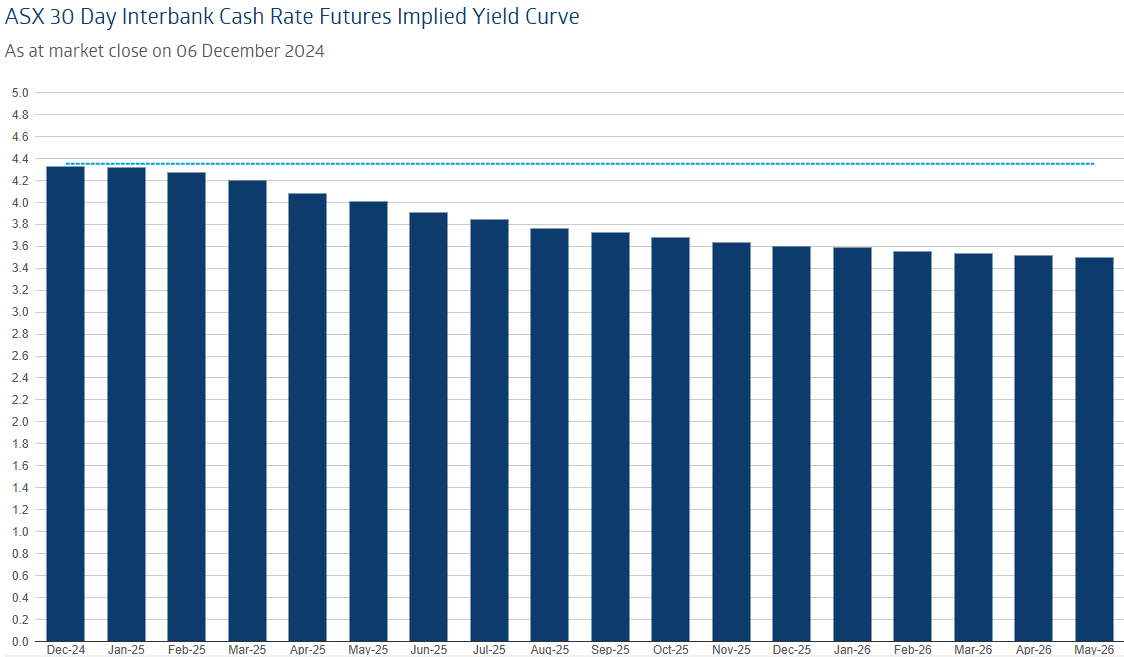

That might be a bit early. The market currently has priced in the first full 25bp cut around March or April next year.

Add Category

Add Category